- The Biomechanics of Load Transfer: The “Hip Loading” Myth vs. Saturation Reality

- Why does my “80% hip load” pack still crush my shoulders?

- The Physiology of Soft Tissue Saturation

- Friction Mechanics and the “Tightening Trap”

- The Role of Meralgia Paresthetica

- Dealibrium Take: Hiking Specs vs. Hunting Reality

- Center of Gravity Physics: The Metabolic Cost of Stability

- Should I pack the meat high or low?

- The “Obusek Effect”: High vs. Low Load Placement

- The Uneven Terrain Trade-Off: The 28% Penalty

- The “Load Shelf” Solution

- The Physics of “Load Lifters”: Analyzing the 45-Degree Vector

- Why do I need straps above my shoulders?

- The Geometry of Relief: Vector Analysis

- Angle Failure Modes

- Frame Height and “Torso Collapse”

- Health & Safety: The Neurology of Heavy Loads

- Why do my fingers go numb?

- Rucksack Palsy: The Silent Nerve Injury

- Meralgia Paresthetica: The Hip Belt Hazard

- Dealibrium Take: Symptom vs. Solution

- Frame Dynamics: Stiffness, Material, and Energy Transmission

- Do I really need a Carbon Fiber frame?

- The Case for Rigidity: Internal vs. External

- Carbon Fiber vs. Aluminum: The Metallurgist’s Guide

- The Insight

- FAQ: Common Questions on Hunting Pack Biomechanics

- Conclusion

- Action List

The backcountry hunter exists in a state of biomechanical contradiction. You spend days moving as a lightweight athlete—climbing thousands of vertical feet, navigating deadfall, and stalking in silence—only to instantly transform into a beast of burden the moment the trigger is pulled. The “pack out” is not merely a hike; it is a violent physical event where the laws of physics conspire against human physiology.

Every hunter knows the specific agony that follows. It begins as a dull ache in the trapezius, migrates to a burning sensation in the lumbar spine, and eventually settles into a crushing, rhythmic fatigue that seems to actively fight every step of elevation gain. For decades, the outdoor industry has addressed this pain with marketing slogans promising “cloud-like comfort” or “revolutionary suspension systems.” However, the physical reality of hauling 100 pounds of elk meat, antlers, and gear across uneven terrain is governed not by marketing copy, but by the immutable laws of leverage, torque, and metabolic efficiency.

The frustration is universal: You bought the expensive pack, you followed the “80% of weight on the hips” rule found in every hiking forum, yet three miles into the haul, your shoulders are numb, your fingers are tingling, and your hips are bruised black and blue. Why does the gear fail to deliver on its promise when the load gets heavy?

The answer lies in a fundamental disconnect between general backpacking wisdom and the extreme demands of hunting. Standard hiking advice—designed for 30-pound loads on groomed trails—catastrophically fails when applied to the dynamic, heavy, and awkward loads inherent to backcountry hunting. We will use scientific research to explain why this happens.

This report serves as the definitive technical guide to hunting backpack weight distribution. We will move beyond the myths. We will utilize military load carriage research, biomechanical engineering data, and physiological studies to deconstruct the science of the heavy haul. We will analyze why the “80% hip load” rule collapses under heavy weight due to soft tissue saturation. We will examine the “Obusek 1997” findings to understand the metabolic trade-offs between high and low centers of gravity. We will calculate the force vectors of load lifters to explain why a 45-degree angle is a mathematical necessity, not a suggestion. By understanding the leverage, torque, and friction coefficients acting upon your musculoskeletal system, you will be equipped to decide between Product A and Product B based on engineering reality rather than hype.

💰Save More with Our Discounts & Coupons!

The Biomechanics of Load Transfer: The “Hip Loading” Myth vs. Saturation Reality

Why does my “80% hip load” pack still crush my shoulders?

The most pervasive metric in backpack fitting is the “80/20 Rule”—the idea that a properly fitted pack should transfer 80% of the load to the hips and leave only 20% on the shoulders. While this ratio is achievable and desirable for standard recreational backpacking loads (25–40 lbs), scientific analysis suggests it is bio-mechanically unsustainable for the heavy loads (60–120 lbs) encountered in hunting. The failure is not necessarily in the pack’s design, but in the physiological limits of the human body.

The Physiology of Soft Tissue Saturation

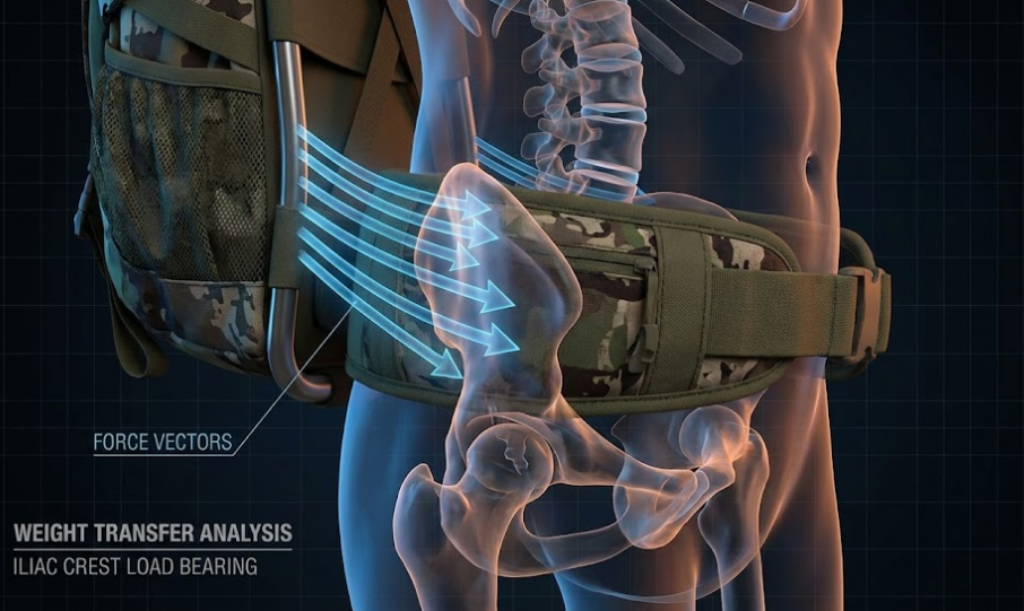

Research into heavy load carriage, particularly from military applications where soldiers routinely carry loads exceeding 40% of their body weight, indicates that the hip belt’s ability to accept load transfer is limited by the compression tolerance of human soft tissue and the friction coefficient of the skin. As the vertical load increases, the downward force eventually overcomes the friction holding the hip belt in place, or the compression becomes so severe that it impedes circulation and nerve function.

When a load exceeds 60–80 lbs (roughly 30-40% of body weight for an average male), the compressive forces on the iliac crest—the bony structure of the hip intended to support the belt—become critical. The “60-70%” figure cited in advanced military load carriage discussions reflects a saturation point. Beyond this threshold, attempting to force 80% of a 100-lb load onto the hips (80 lbs of point pressure) leads to rapid onset of physiological failure.

Load Transfer Efficiency Drop-off:

Studies on “Lumbosacral Joint Compression Force Profile” indicate that while hip belts significantly reduce spinal compression, the efficacy plateaus. The soft tissue surrounding the iliac crest compresses until it bottoms out against the bone. Once this compression limit is reached, any additional weight added to the pack cannot be effectively transferred to the hips without causing the belt to slip downward. This slippage forces the load back onto the shoulder straps, regardless of how tight the user cinches the belt.

Friction Mechanics and the “Tightening Trap”

The hip belt functions through a combination of mechanical interference (resting on the shelf of the hip bone) and friction. To support a vertical load (Fv) of 80 lbs purely via friction, the normal force (tightness of the belt) (Fn) must satisfy the equation:

Where µ is the coefficient of static friction between the belt materials and the user’s clothing or skin. As the weight of the elk quarter increases (Fv goes up), the user must increase Fn (tighten the belt) to prevent slippage. However, there is a biological limit to Fn. Excessive tightening leads to the compression of the femoral nerve and restriction of lymphatic and venous return from the legs, a condition that can lead to rapid fatigue and injury.

This biomechanical reality dictates that for loads exceeding 80 lbs, the shoulders must take on 30-40% of the burden to preserve the hips for locomotion. The hunting pack must be designed not just to “transfer load,” but to manage this dynamic interplay where the shoulder straps act as essential load-bearing components rather than just stabilizers.

Pro-Tip: The “Shrug and Cinch” Maneuver

When your hips start to burn under a heavy pack-out, don’t just tighten the belt. Stop, loosen the shoulder straps completely. Shrug your shoulders high to physically lift the pack weight off your hips. While shrugging, re-cinch the hip belt directly over the iliac crest (not the waist). Then, drop your shoulders and settle the shoulder straps back down. This resets the “friction shelf” and can buy you another mile of comfort.

💰Save More with Our Discounts & Coupons!

The Role of Meralgia Paresthetica

One of the most common yet misdiagnosed injuries in heavy packing is meralgia paresthetica, a condition characterized by burning pain, numbness, and tingling on the outer thigh. This is caused by the compression of the Lateral Femoral Cutaneous Nerve (LFCN), which passes under the inguinal ligament and over the iliac crest.

Mechanism of Injury:

When a hunter overloads the hip belt (attempting to hit that 80% target with a 100lb load), they instinctively overtighten the belt to prevent slipping. If the belt is worn too low or is too narrow, it crushes the LFCN against the pelvic bone. This is a direct result of misunderstanding load distribution limits.

Prevention Strategy:

The solution is twofold:

- Positional Accuracy: The hip belt must be centered over the iliac crest, cupping the bone, rather than squeezing the waist or hips below it.

- Load Sharing: By purposefully engaging the load lifters to take 30-40% of the weight onto the shoulders, the hunter reduces the required hoop tension on the hip belt, sparing the LFCN.9

Dealibrium Take: Hiking Specs vs. Hunting Reality

| Specification | Typical Hiking Advice | The Hunting Reality (Heavy Load Physics) |

| Weight Distribution | 80% Hips / 20% Shoulders | 60-70% Hips / 30-40% Shoulders (Hips saturate at extreme loads) |

| Hip Belt Function | “Comfort and padding” | Structural Clamp (Must resist vertical shear forces >80 lbs) |

| Tightening Strategy | “Snug fit” | Variable Tension (Must manage friction vs. nerve compression) |

| Injury Risk | Chafing, Fatigue | Nerve Damage (Meralgia Paresthetica, Rucksack Palsy) |

This helps you decide between Product A (a plush, soft-belted hiking pack) and Product B (a rigid, structured hunting pack). For loads under 40 lbs, Product A is superior. For the 100-lb pack out, Product B’s ability to clamp the iliac crest without collapsing is essential.

Center of Gravity Physics: The Metabolic Cost of Stability

Should I pack the meat high or low?

This is perhaps the most debated topic in backpack hunting. Conventional wisdom often contradicts physics. To answer this, we must look at the metabolic cost of transport—essentially, how many calories your body burns to move a specific weight over a specific distance.

The “Obusek Effect”: High vs. Low Load Placement

A pivotal study referenced in military load carriage literature is “The relationship of backpack center of mass location to the metabolic cost of load carriage” by Obusek et al. (1997). This research provides a definitive answer regarding metabolic efficiency on flat or moderate terrain.

The Findings:

The study found that a high and tight center of mass (COM) is the most metabolically efficient position for heavy load carriage.

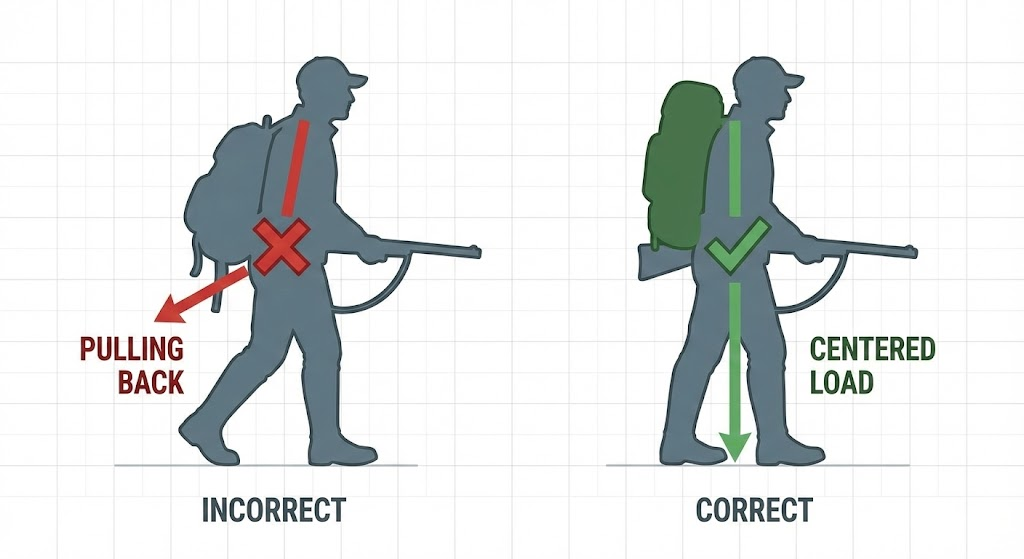

- The Biomechanics: A high COM aligns the load with the body’s natural vertical axis. When the load is high, the hunter only needs to lean forward slightly to bring the combined center of mass (body + pack) over the feet.

- The Metabolic Advantage: Conversely, carrying a load low on the back forces the hunter to lean forward significantly to counterbalance the weight. This sustained forward flexion engages the erector spinae and hip extensors in a constant isometric contraction to prevent toppling. This unnecessary muscle activation burns oxygen and glycogen, increasing the metabolic cost of walking even on flat ground.

Therefore, for maximum efficiency, the heaviest portion of the load (the meat) should be placed high between the shoulder blades.

The Uneven Terrain Trade-Off: The 28% Penalty

However, the “High COM” rule has a critical point of failure: Uneven Terrain. Hunting rarely happens on flat treadmills. It happens on scree fields, deadfall, and steep side-hills. On this terrain, a high COM becomes a liability.

The Physics of Instability:

A high COM raises the system’s “inverted pendulum.” This makes the hunter top-heavy. As the terrain shifts beneath the feet, a high load creates a longer lever arm for lateral forces (swaying).

- Co-Activation Cost: To stabilize this swaying load, the body must fire stabilizer muscles in the ankles, knees, and core rapidly and simultaneously. Research indicates that walking on uneven terrain increases metabolic energy expenditure by approximately 28% compared to smooth surfaces.

- The Dilemma: A high load saves energy on posture but wastes energy on stabilization. A low load wastes energy on posture (lean) but saves energy on stabilization (lower center of gravity).

💰Save More with Our Discounts & Coupons!

The “Load Shelf” Solution

This biomechanical conflict explains the rise of the “Load Shelf” or “Meat Shelf” design in modern hunting packs (Stone Glacier, Mystery Ranch, Exo Mtn Gear). These systems allow the densest weight (meat) to be placed between the bag and the frame, rather than inside the bag.

Minimizing the Moment Arm:

The primary advantage of the load shelf is the reduction of the Moment Arm (d). Torque (T) is defined as Force (F) * Distance (d).

- Scenario A (Hiking Pack): A 50 lb elk quarter is placed inside the main bag. It sits behind a hydration bladder, a spotting scope, and layers of fabric. It is 6 inches from the spine. Torque = 50 lbs x 6 in = 300 in-lbs.

- Scenario B (Hunting Pack with Shelf): The same quarter is sandwiched directly against the frame. It is 1 inch from the spine. Torque = 50 lbs x 1 in = 50 in-lbs.

By placing the load directly against the frame, the “moment arm” is minimized. This drastically reduces the backward pull on the shoulders and spine. Stone Glacier’s founder, Kurt Racicot, demonstrated simulations showing that proper shelf loading could reduce the “felt leverage” of a 76-pound load from 32 pounds of pull-back force to just 14 pounds.

Operational Synthesis:

For the hunter, the data suggests a dynamic approach:

- The Approach: On the hike in, or on good trails, keep gear relatively high to maximize the Obusek efficiency.

- The Stalk/Steep Descent: When navigating deadfall or steep side-hills, lower the heavy meat load slightly to the mid-back (but keep it tight against the frame) to lower the center of gravity and prevent falls. The metabolic cost of the forward lean is preferable to the catastrophic cost of a fall or the energy wasted stabilizing a swaying load.

This helps you decide between Product A (a standard pack where the load shifts) and Product B (a pack with a dedicated load shelf). Product B offers the mechanical advantage necessary to manipulate the center of gravity for different phases of the hunt.

The Physics of “Load Lifters”: Analyzing the 45-Degree Vector

Why do I need straps above my shoulders?

“Load lifters” are perhaps the most misunderstood component of a backpack. Many hikers view them as mere stabilizers to keep the pack from flopping backward. In reality, they are essential suspension levers designed to alter the vector forces acting on the shoulder girdle. Their function is mathematical, not just practical.

The Geometry of Relief: Vector Analysis

When a backpack pulls back, the shoulder strap exerts two distinct forces on the anterior (front) of the shoulder:

- Horizontal Force (Fx): Pulling the shoulder back.

- Vertical Force (Fy): Pulling the shoulder down.

The downward vertical force (Fy) is the enemy. It compresses the clavicle, restricts blood flow, and crushes the brachial plexus nerves. The load lifter strap is designed to counteract this Fy.

The 45-Degree Theorem:

For load lifters to function, they must form a 45-degree angle extending upward and backward from the top of the shoulder to the frame of the pack.18

- Vector Decomposition: The tension in the load lifter strap (T) creates an upward vector component: Ty = T sin(45°).

- The Lift: This Ty component literally lifts the shoulder strap up and off the top of the shoulder. It transforms the shoulder strap from a crushing weight into a front-facing brace. The weight is transferred from the top of the shoulders (trapezius) to the front of the chest (sternum) and, crucially, driven down into the frame and hip belt.

Angle Failure Modes

The physics dictate that the angle is critical:

- Angle < 30 degrees: If the angle is too shallow (flat), the strap pulls primarily horizontally (Tx). This pulls the pack closer to the back (stabilization) but provides zero lift (Ty≈0). The weight remains crushing the shoulders.

- Angle > 60 degrees: If the angle is too steep, the strap pulls the shoulder straps entirely off the body, leading to instability and “pack sway.”

Frame Height and “Torso Collapse”

This physics requirement explains why hunting packs look different from hiking packs. For a load lifter to create a 45-degree angle, the frame must extend above the user’s shoulders.

The “Torso Collapse” Failure:

In frameless packs or packs with frames shorter than the torso (common in ultralight hiking gear), tightening the “load lifters” only pulls the shoulder straps tighter against the collarbone. There is no rigid point above the shoulder to pull against. This results in “torso collapse,” where the pack slumps, the effective torso length shortens, and weight transfers back onto the shoulders.

Hunting Application:

This is why a hunting pack must feature a taller frame (typically 24–28 inches) compared to a recreational hiking pack. The extra height is not for capacity; it is the necessary anchor point for the load lifter to generate the lift vector required for a 100-lb load.

Pro-Tip: The Mirror Check

Before your hunt, load your pack with 50 lbs and stand sideways in front of a mirror. Look at the angle of the strap connecting your shoulder strap to the frame. If it is flat (horizontal) or angling down, your frame is too short or your torso setting is wrong. You will be in agony on the pack out. You need to see daylight between the top of your shoulder and the strap.

💰Save More with Our Discounts & Coupons!

Health & Safety: The Neurology of Heavy Loads

Why do my fingers go numb?

Carrying heavy loads for prolonged periods carries risks far beyond simple muscle fatigue. There are specific neurological injuries associated with improper weight distribution that every hunter must understand to prevent permanent damage.

Rucksack Palsy: The Silent Nerve Injury

Rucksack Palsy is a compression injury to the brachial plexus nerves.

- Anatomy: The brachial plexus is a network of nerves that originates in the neck and passes between the clavicle (collarbone) and the first rib before supplying the arm and hand.

- Mechanism: When the shoulder straps of a heavy pack dig into the trap/clavicle area, they compress the upper trunk of the brachial plexus (specifically the C5-C6 roots).

- Symptoms: The injury typically presents as paresthesia (pins and needles), numbness, and weakness in the arm or hand. In severe cases, it can lead to “winged scapula,” a paralysis of the serratus anterior muscle caused by damage to the Long Thoracic Nerve.

- Prevention: This is the critical health reason for the “Load Lifter” physics discussed above. By creating that 45-degree lift vector, the load lifters remove the direct crushing pressure from the brachial plexus tunnel. If your fingers start to tingle, your pack fit is failing, and nerve damage is imminent.

Meralgia Paresthetica: The Hip Belt Hazard

While we emphasize transferring weight to the hips, over-loading or improperly positioning the hip belt causes Meralgia Paresthetica.

- Anatomy: The Lateral Femoral Cutaneous Nerve (LFCN) is a sensory nerve that runs over the brim of the pelvis (iliac crest) and under the inguinal ligament.

- Mechanism: A hip belt that is worn too low (compressing the soft tissue below the iliac crest) or overtightened (to compensate for a slipping load) crushes the LFCN against the pelvic bone.

- Symptoms: A burning pain, numbness, or “stinging” sensation on the outer thigh. It is purely sensory but can be excruciating and debilitating during a hike.

- The Fix: The hip belt must be centered over the iliac crest, cupping the bone. The belt effectively “hangs” on the skeletal structure. The conical shape of the belt must match the cant of the hips to prevent downward slippage without excessive tightening. If you have to cinch the belt until you can’t breathe to keep it up, the pack’s lumbar pad or belt shape is likely incompatible with your anatomy.

Dealibrium Take: Symptom vs. Solution

| Symptom | Diagnosis | Mechanical Cause | The Solution |

| Numb Fingers / Arm Weakness | Rucksack Palsy | Shoulder strap compressing clavicle | Tighten Load Lifters (need 45° angle); Shift weight to hips. |

| Burning Outer Thigh | Meralgia Paresthetica | Hip belt crushing LFCN nerve | Reposition belt higher on Iliac Crest; Loosen belt slightly and engage shoulders. |

| Lumbar “Fire” | Erector Spinae Fatigue | Center of Gravity too low/far back | Utilize Load Shelf to move meat closer to spine and higher up. |

| Bruised Hip Bones | Skin Shear / Pressure | Belt slipping under load | Use “Shrug and Cinch” technique; Check lumbar pad friction. |

Frame Dynamics: Stiffness, Material, and Energy Transmission

Do I really need a Carbon Fiber frame?

The debate between frame materials—specifically Carbon Fiber versus Aluminum—is often reduced to weight. However, for the hunter carrying 100 lbs, the primary consideration should be stiffness and energy transmission.

The Case for Rigidity: Internal vs. External

The debate between internal and external frames is settled by the magnitude of the load.

- Loads < 40 lbs: Flexible internal frames allow for dynamic gait and comfort. They move with the body.

- Loads > 80 lbs: Rigidity becomes the paramount virtue.

- Energy Leakage: A flexible frame “leaks” energy. As the hunter steps, a flexible frame bows and rebounds. This oscillation is out of phase with the walker’s gait, requiring additional energy to dampen the bounce.

- Load Transfer Efficiency: A rigid frame acts as a solid column. Downward force applied to the load lifters is transmitted directly to the lumbar pad and hip belt without dissipation. Studies show that external or rigid-internal frames (like modern hunting hybrids) significantly reduce the muscle activation required to support heavy loads compared to flexible stays.

Carbon Fiber vs. Aluminum: The Metallurgist’s Guide

Modern hunting packs (Kuiu, Stone Glacier) utilize Carbon Fiber, while others (Barney’s, Mystery Ranch, Exo Mtn Gear) often use Aluminum or composite stays.

Carbon Fiber:

- Pros: Superior strength-to-weight ratio. Extreme vertical rigidity prevents “barreling” (bulging against the spine) under heavy compression. It creates a highly efficient column for load transfer.

- Cons: It is brittle under catastrophic impact (e.g., falling on a rock). It cannot be reshaped.

- Best For: Ultralight hunters who prioritize weight savings and vertical stiffness above all else.

Aluminum (7075 / Aircraft Grade):

- Pros: High ductility. Crucially, aluminum stays can be removed and bent to match the user’s specific spinal curvature (lordosis).

- The Fit Advantage: By molding the stays to the back, the contact surface area is maximized. This increases friction and mechanical locking, preventing the pack from sliding down under heavy loads without needing to overtighten the belt.

- Cons: Heavier than carbon. Can deform permanently if overloaded dynamically.

- Best For: Hunters with significant spinal curvature (flat back or deep sway back) who need a custom fit to prevent slippage.

The Insight

For the heaviest loads, the ability to shape aluminum stays to lock into the lumbar curve can offer superior non-slip performance compared to the flat, rigid profile of carbon, despite the weight penalty. Physics favors the custom fit for friction management.

💰Save More with Our Discounts & Coupons!

FAQ: Common Questions on Hunting Pack Biomechanics

This is a result of the occlusive effect of the pack against your back, preventing evaporative cooling. When carrying heavy loads, your metabolic heat output skyrockets. If the pack fits too flush against the spine without ventilation channels, sweat cannot evaporate (the “wet-out” effect). This leads to rapid cooling when you stop. External frames or “suspended mesh” designs create an air gap (chimney effect) to mitigate this, though they push the Center of Mass further away, increasing torque. It is a trade-off between thermal regulation and load leverage.

Technically yes, but hiking packs are designed for loads of 30-50 lbs. Their frames often lack the vertical rigidity to support 100+ lbs without collapsing, and they lack a load shelf to keep dense meat against the spine. This increases the “moment arm” (leverage) pulling you backward. A hiking pack with a 100lb load will suffer from “torso collapse,” rendering the load lifters useless and dumping 100% of the weight onto your shoulders.

For efficiency on trails, carry heavy weight high (between shoulder blades) to align with your center of gravity and reduce metabolic cost (Obusek 1997). For stability on steep, uneven off-trail terrain, lower the weight slightly to the mid-back to prevent being thrown off balance, but never let it sag to the bottom of the pack.

Biomechanically, yes. A “double pack” or front-loading vest balances the center of mass over the hips, eliminating the forward lean and reducing energy expenditure. However, in a hunting context, front packs interfere with weapon manipulation, glassing, and traversing rough terrain. The backpack remains the best compromise for field utility, despite the metabolic penalty of the counter-balance lean.

This is often due to the belt sliding down and resting on the soft tissue or the belt being too flat for your hip shape. Ensure the belt is centered over the iliac crest (the bony ridge), cupping it. If bruising persists, check if the lumbar pad is pushing the pack too far away, or if the belt lacks sufficient stiffness to hold the load without overtightening. A stiff belt distributes force; a soft belt bunches and creates pressure points.

Conclusion

The science of hunting backpack weight distribution is not about achieving a feeling of weightlessness—gravity cannot be cheated. It is about mechanical efficiency and physiological preservation. By understanding the forces at play, you can manipulate them to your advantage.

- Leverage Management is King: The Load Shelf is the single most important feature for a hunting pack because it minimizes the Moment Arm. Reducing the distance of a 100-lb load from your spine by just 2 inches can reduce the backward torque on your spine by over 50%. This saves your back and your energy.

- The “80/20” Rule Has a Limit: At hunting weights (80+ lbs), the hips reach a saturation point dictated by soft tissue compression and friction limits. A realistic goal is 60-70% hip loading; your shoulders will and must do some work to stabilize the load and prevent nerve compression injuries like Meralgia Paresthetica.

- Terrain Dictates Center of Gravity: While a high Center of Mass is metabolically efficient (Obusek 1997), the 28% metabolic penalty of walking on uneven terrain implies that stability often trumps theoretical efficiency. Pack meat high for the trail out, but keep it mid-back and tight for the stalk or steep descent.

Bold Takeaway: Do not buy a hunting pack based on how it feels empty in the store. Buy it based on its frame height, load shelf design, and the ability of its suspension to create a 45-degree load lifter angle when loaded with 80 pounds of sandbags. Physics doesn’t care about brand names.

Action List

- Measure Your Torso: Find your C7 vertebra and Iliac Crest. Ensure your pack frame is at least 2-4 inches taller than this measurement to ensure functional load lifters.

- Test with Sandbags: Before your hunt, load your pack with 60lbs of sand (or salt). Adjust the harness until you see a 45-degree angle on the load lifters.

- Practice the “Shrug”: Learn to reset your hip belt on the fly without stopping.

- Inspect Your Frame: If using Aluminum stays, bend them to match the curve of your lower back for increased contact patch and friction.