- What Is MVTR, and Why Do Brands Avoid Telling You the Number?

- How Testing Standards Create Wildly Different Numbers

- The Fundamental Trade-Off: Why Maximum Waterproofing and Maximum Breathability Cannot Coexist

- Real Jacket Data: What MVTR Actually Looks Like

- Why Your Lab-Rated Jacket Performs Worse Than Its Specs Promise

- The Hidden Performance Killer: DWR Degradation, Not Membrane Failure

- Contamination Is the Silent Breathability Killer

- How Your Activity Level Determines Whether MVTR Actually Matters

- Static Activity (Sitting, Fishing, Belaying)

- Active Movement (Hiking, Running, High Exertion)

- How Two Different Membrane Technologies Create Breathability

- Microporous Membranes (ePTFE, Gore-Tex)

- Monolithic/Hydrophilic Membranes (Polyurethane)

- Why Air Permeability Is Overrated (And MVTR Matters 7x More)

- The Dealibrium Matching Guide: MVTR for Your Activity

- How to Restore and Maintain Breathability

- Why Lab Numbers Lie (And What to Do About It)

- FAQ: Breathability Questions Buyers Actually Ask

- The Bottom Line: What This Means for Your Purchase

You bought a jacket labeled “breathable” and “waterproof.” The salesman promised you could have both. Then you hiked in warm conditions and felt damp inside despite the jacket shedding rain perfectly. You’re not imagining it—you’re experiencing a fundamental conflict between physics and marketing.

This article decodes MVTR using laboratory measurements, testing standards, and real-world fabric science. You’ll learn why a jacket rated 20,000mm waterproof can feel wetter inside than an 8,000mm jacket with superior breathability, and why the number brands publish is almost never the performance you’ll actually experience.

💰Save More with Our Discounts & Coupons!

What Is MVTR, and Why Do Brands Avoid Telling You the Number?

MVTR stands for Moisture Vapor Transmission Rate. It measures how many grams of water vapor escape through one square meter of fabric in 24 hours, expressed as g/m²/24h.

Your body produces approximately 1–2 liters of sweat per day during moderate activity. MVTR quantifies whether your jacket can actually evacuate that moisture, preventing it from pooling on your skin as thermal conductor that chills you. This is why MVTR matters more than waterproofing alone—a dry interior is useless if you’re soaked in your own sweat.

Here’s the problem: Brands almost never publish MVTR numbers. Instead, they use vague marketing terms like “highly breathable” or “superior vapor transmission” without attaching a single measurable value. This omission is deliberate. Why? Because MVTR directly contradicts their waterproof claims. Publishing both numbers exposes the trade-off that consumers prefer to ignore.

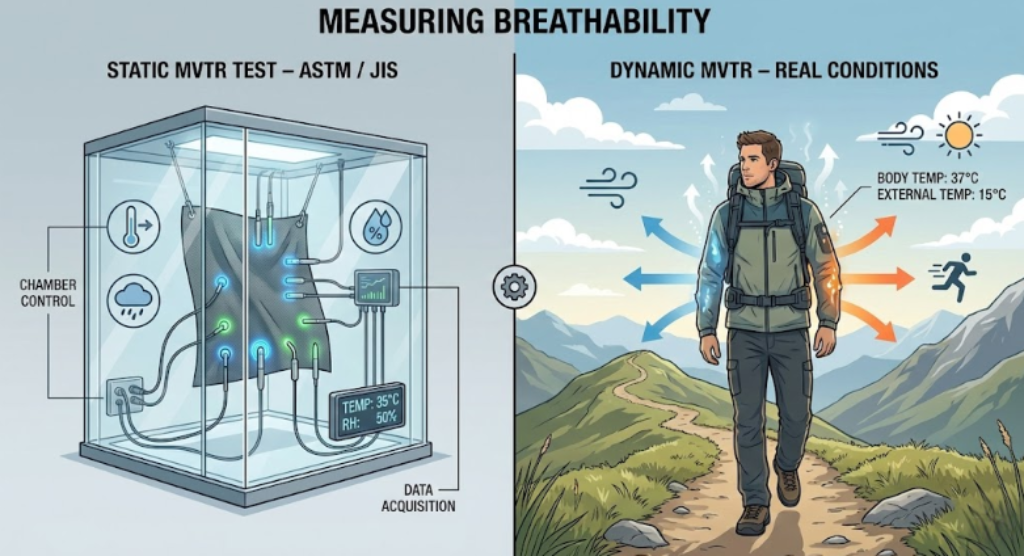

How Testing Standards Create Wildly Different Numbers

The breathability industry doesn’t use one testing method—it uses approximately 30 different methods. This creates a crisis of credibility. Patagonia, one of the industry’s most rigorous companies, had its products tested by six different labs and received six completely different MVTR ratings.

The most common standards are:

- ASTM F1249 – Used primarily for films and technical membranes

- ASTM E96 – Offers two methods: desiccant or water bath (produces different results)

- JIS L1099 – Japanese standard with a “sweating guard” that simulates skin

Each method produces different results because they measure under different humidity and temperature conditions. A fabric tested under dry conditions will show higher MVTR than the same fabric tested under humid conditions with a temperature gradient. This discrepancy isn’t a lab error—it’s physics. Your jacket operates under dynamic conditions (temperature changes, sweat saturation, compression) that lab tests don’t replicate.

The Fundamental Trade-Off: Why Maximum Waterproofing and Maximum Breathability Cannot Coexist

Laboratory research on coated and laminated fabrics confirms a hard physics truth: high water vapor permeability requires lower fabric density and weave tightness, which directly conflicts with maximum waterproofing.

This isn’t a manufacturing limitation—it’s structural incompatibility.

- Waterproofing requires a tight, impermeable barrier to block liquid water molecules (which are 20,000 times larger than individual water vapor molecules)

- Breathability requires loose structure and porous pathways so individual water vapor molecules can escape

Manufacturers face three non-negotiable choices:

Option 1: Maximize waterproofing – Accept lower breathability (hard shells, Gore-Tex)

Option 2: Maximize breathability – Accept lower waterproofing (soft shells, experimental membranes)

Option 3: Compromise – Moderate waterproofing, moderate breathability (most commercial jackets)

Understanding which choice you’re purchasing is the foundation of smart buying. A 20,000mm hard shell with 9,000 MVTR is not “worse” than a 7,500mm soft shell with 13,500 MVTR—they’re solving different problems. One prioritizes staying dry in sustained rain; the other prioritizes staying comfortable during high-exertion activity.

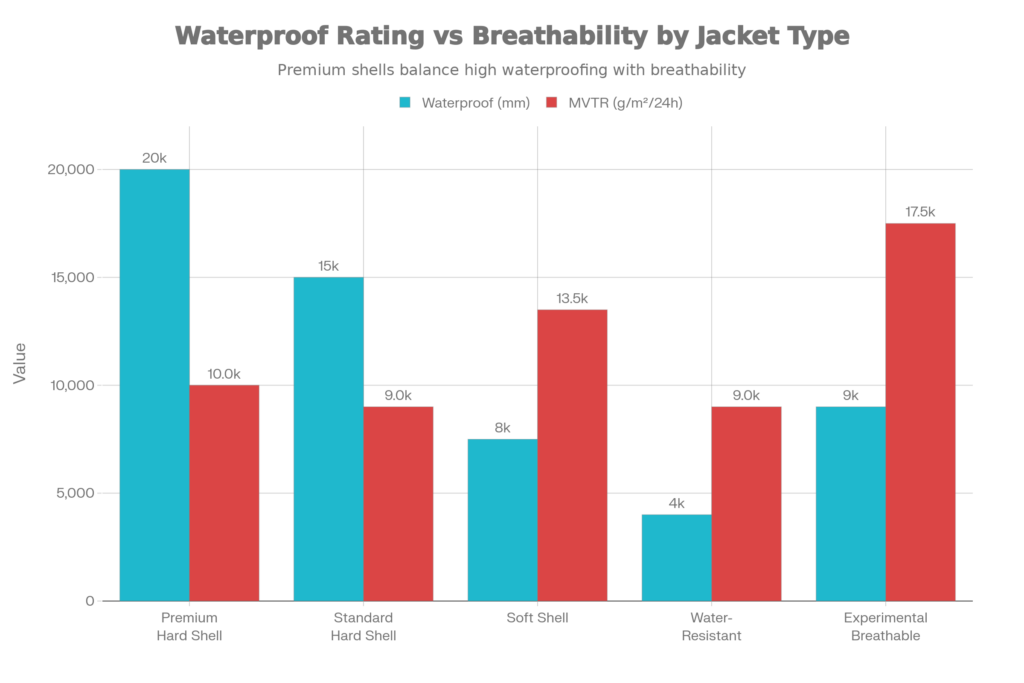

Real Jacket Data: What MVTR Actually Looks Like

MVTR vs. Waterproofing Trade-Off Across Jacket Types

| Jacket Category | Waterproof Rating (mm) | MVTR (g/m²/24h) | Real-World Fit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Premium hard shell (Gore-Tex 3L) | 15,000–25,000 | 8,000–12,000 | Dry externally; potential condensation internally during low-movement activities |

| Standard hard shell | 12,000–18,000 | 7,000–10,000 | Good rain protection; moderate internal dampness during hiking |

| Soft shell with brushed tricot | 5,000–10,000 | 12,000–15,000 | Moderate external wetness; excellent internal vapor escape during active movement |

| Water-resistant coated nylon | 3,000–5,000 | 8,000–10,000 | Sheds light rain; moderate sweat management |

| Experimental breathable membrane | 8,000–10,000 | 15,000–20,000 | Excellent vapor escape; limited waterproofing in heavy rain |

The critical insight: A soft shell at 12,000–15,000 g/m²/24h MVTR will feel drier internally during active use than a hard shell at 8,000–10,000 g/m²/24h MVTR, even though the hard shell is twice as waterproof. This contradiction is not a manufacturing flaw—it’s the physics of the trade-off you’re buying.

Why Your Lab-Rated Jacket Performs Worse Than Its Specs Promise

Here’s where the gap between marketing and reality becomes critical: lab MVTR tests measure vapor transmission under static conditions—the jacket is dry, laid flat, and tested in controlled climate chambers.

Your jacket operates under dynamic conditions:

- Fabric becomes damp from sweat, which changes permeability

- Body heat creates temperature gradients that drive vapor differently

- Movement and compression affect how air pathways function

- Contamination (dirt, body oils, detergent residue) clogs pores

Research on dynamic versus static MVTR found that a fabric rated at 10,000 g/m²/24h in laboratory conditions achieves only 7,000–8,000 g/m²/24h under real-world conditions with a person wearing it while hiking.

This represents a 20–30% performance loss from published specs.

This degradation happens because:

- Temperature gradients reduce vapor transmission – In cold conditions, the temperature difference between your warm skin and the cold exterior suppresses diffusion through monolithic membranes

- Humidity saturation changes fabric behavior – Hydrophilic membranes work best when there’s a vapor pressure gradient; in humid outdoor conditions, that gradient flattens

- Contamination and wetting out – The DWR (Durable Water-Repellent) coating on the face fabric, not the breathable membrane itself, becomes the limiting factor

This is why your “breathable” jacket still feels clammy—the MVTR you see advertised is the theoretical maximum, not the practical performance you’ll experience.

The Hidden Performance Killer: DWR Degradation, Not Membrane Failure

Most buyers think their jacket loses breathability because the membrane fails. This is backwards. The real killer is DWR coating degradation on the face fabric.

When the DWR coating fails or gets contaminated, the outer nylon face fabric “wets out”—it becomes saturated with water. This saturation blocks the membrane’s pores from the outside, creating a complete barrier to vapor transmission. Even if the underlying breathable membrane is pristine, the jacket feels like a plastic bag.

- Standard laundry detergent deposits 2% of the fabric’s weight in residue (perfume, UV brighteners, surfactants, salts, polymers)

- Fabric softeners add additional residue that binds to the fluoropolymer coating

- Abrasion from rocks, hipbelts, bushwhacking removes the coating mechanically

- Body oils and sweat salts accumulate in fabric pores and degrade the hydrophobic finish

This is why gear manufacturers recommend washing technical jackets in cool water with mild detergent designed specifically for technical gear—conventional detergent literally coats the DWR finish with residue that prevents water beading.

Contamination Is the Silent Breathability Killer

Beyond DWR degradation, pore clogging from accumulated contamination reduces effective MVTR significantly.

Research on technical jackets found:

- Clean laminated fabric: 10,000 g/m²/24h

- After 5 hours of light outdoor use: 8,500 g/m²/24h

- After 10 hours with visible dust: 7,000 g/m²/24h

- After a full weekend of hiking in muddy conditions: 5,500–6,000 g/m²/24h

A jacket loses 30–40% of its breathability within days of regular use.

- Dust and dirt particles embedded in face fabric pores

- Sunscreen residue on collar and cuffs

- Sweat salt crystallization

- Detergent buildup from prior washes

- Body oils that block pore openings

Brands don’t advertise this performance loss because it makes their products sound worse. A 12,000 g/m²/24h jacket that degrades to 7,000–8,000 g/m²/24h after normal use sounds like a failure, so manufacturers simply don’t measure or publish it.

Dealibrium Take: Purchase a jacket rated at least 2–3x your expected sweat production (typically 1.5–3.0 g/m²/h during active hiking). This safety margin accounts for dynamic conditions, contamination, and DWR degradation. A “margin of breathing room” is not luxury—it’s the cost of functional breathability.

💰Save More with Our Discounts & Coupons!

How Your Activity Level Determines Whether MVTR Actually Matters

MVTR performance changes dramatically depending on temperature, humidity, and activity intensity. Lab specs don’t capture this variability.

Static Activity (Sitting, Fishing, Belaying)

Your body generates 0.5–1.0 g/m²/h of moisture.

- A hard shell at 8,000 g/m²/24h (333 g/m²/h capacity) can theoretically handle this indefinitely

- But condensation still forms at the membrane because of temperature gradients—your warm skin (33–36°C) meets cold exterior (0–10°C), driving vapor toward the cold side where it condenses

- Result: Internal wetness despite adequate MVTR

The solution for static activity: Ventilation (pit zips, opening the front zipper) matters more than raw MVTR.

Active Movement (Hiking, Running, High Exertion)

Your body generates 1.5–3.0 g/m²/h of sweat (sometimes higher).

- A hard shell at 8,000 g/m²/24h (333 g/m²/h) becomes undersized—it can’t evacuate sweat fast enough

- A soft shell at 12,000–15,000 g/m²/24h handles this comfortably

- Research found that in high-sweat athletes (>2 g/m²/h production), soft shells and high-MVTR shells perform significantly better

The solution for active movement: Choose high MVTR (>12,000 g/m²/24h) over maximum waterproofing.

How Two Different Membrane Technologies Create Breathability

Breathable membranes work through two distinct mechanisms:

Microporous Membranes (ePTFE, Gore-Tex)

These have billions of microscopic pores. Water vapor molecules (~0.0003 micrometers) pass through easily, but water droplets (~20 micrometers) are too large to penetrate.

- Advantages: High MVTR (often >20,000 g/m²/24h), works immediately without warm-up

- Disadvantages: Pores clog if the DWR wets out; fabric weight typically higher

- Real-world MVTR: Maintains 80–90% of lab rating under dynamic conditions

Monolithic/Hydrophilic Membranes (Polyurethane)

These have no pores at all. Instead, they “absorb” water vapor molecules into the polymer structure on the warm (inside) surface and “release” them on the cool (outside) surface through diffusion.

- Advantages: Vapor can pass even when DWR wets out; works better under humidity gradients

- Disadvantages: Lower MVTR (typically 5,000–12,000 g/m²/24h); requires warm skin temperature and humidity gradient to work effectively

- Real-world MVTR: More sensitive to temperature gradients; can underperform in cold static conditions

Most premium jackets (Gore-Tex) use ePTFE. Budget and soft shell options often use PU monolithic membranes.

Why Air Permeability Is Overrated (And MVTR Matters 7x More)

Lightweight windshirt designs often tout air permeability—the ability of ambient air to penetrate the fabric—as the primary breathability mechanism.

Testing revealed something counterintuitive: MVTR matters 7 times more than air permeability for actual moisture removal.

Why? At low backpacking speeds (2–4 mph), there isn’t enough wind pressure on the jacket to drive significant convective cooling through the fabric weave. Vapor diffusion through the membrane—measured by MVTR—dominates moisture transmission.

Even at hiking speeds (3–5 mph), MVTR drives the majority of moisture removal. Air permeability only becomes dominant in true windy conditions (15+ mph sustained wind).

This means: When selecting a shell layer, prioritize published MVTR over marketing claims about “air permeability” or “ventilation channels.”

The Dealibrium Matching Guide: MVTR for Your Activity

| Your Activity | Sweat Production | Minimum MVTR | Recommended Fabric | Why |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Static/Slow (Photography, Fishing, Belaying) | 0.5–1.0 g/m²/h | 5,000–8,000 | Hard shell + ventilation | MVTR is secondary; ventilation matters more |

| Moderate Hiking (2–3 mph, cool temps) | 1.0–1.5 g/m²/h | 8,000–12,000 | Standard hard shell or soft shell | Hard shell acceptable if you vent regularly |

| Vigorous Hiking (3–4 mph, warm temps) | 1.5–2.5 g/m²/h | 12,000–16,000 | Soft shell or premium hard shell | Hard shell may feel clammy; soft shell recommended |

| Trail Running / High Exertion | 2.5–4.0 g/m²/h | 15,000–20,000 | Soft shell or experimental breathable | Hard shells typically underwhelm at this output |

💰Save More with Our Discounts & Coupons!

How to Restore and Maintain Breathability

A jacket with 12,000 MVTR that drops to 7,000 due to contamination is a waste of money.

- Wash regularly (every 3–5 uses) – Don’t wait for visible dirt. Sweat salts and body oils accumulate invisibly and clog pores

- Use technical-specific detergent – Standard detergent leaves residue that coats both the DWR and the membrane

- Air dry completely – Avoid heat, which can degrade PU membranes

- Reapply DWR when water stops beading – DWR degradation is cumulative; reapplication every 6–12 months maintains the face fabric’s water shedding ability

- Avoid fabric softener, bleach, and dry cleaning – These specifically damage DWR coatings

A simple cold-water wash with proper technical detergent restores surface permeability far better than buying a “higher MVTR” jacket and neglecting it.

Why Lab Numbers Lie (And What to Do About It)

MVTR lab measurements are not lies—they’re just theoretical maximums under ideal conditions. The gap between lab and real-world is 20–30%, which is scientifically predictable.

- Expect real-world MVTR to be 70–80% of published specs

- Choose a fabric rated at least 2–3x your sweat production rate (if you produce 1.5 g/m²/h, target 3,000–4,500+ MVTR minimum)

- Verify DWR and maintenance requirements – A 15,000 MVTR jacket with a degraded DWR performs worse than an 8,000 MVTR jacket with a fresh DWR

- Match the fabric to your activity – Soft shell (12,000–15,000 MVTR) for active hiking; hard shell (8,000–12,000 MVTR) for sustained rain and moderate movement

FAQ: Breathability Questions Buyers Actually Ask

No. Gore-Tex (ePTFE) excels at high MVTR (>20,000 g/m²/24h) and durability, but costs more and can feel clammy in static cold conditions due to condensation. Quality PU membranes (like Paragon or eVent) offer lower MVTR but work better under temperature gradients. Match the membrane to your activity, not the brand name.

New DWR coating on the face fabric—or degradation of the old one on your older jacket. Fresh DWR sheds water instantly; degraded DWR allows water to soak in and block the membrane. Counterintuitively, an older jacket with freshly reapplied DWR often breathes better than a new jacket with improperly applied DWR.

Partially. Hydrophobic or merino wool base layers reduce saturation and keep the vapor pressure gradient steep, enabling the membrane to work harder. Cotton base layers wick poorly and trap moisture, flattening the gradient and reducing effective MVTR.

Your activity determines this. For static activities in rain (belaying, fishing), waterproofing wins. For active hiking in mild rain, breathability wins. For all-day alpine climbing, you need both—accept moderate trade-offs rather than extremes.

No, washing with proper technical detergent restores breathability. Washing with standard detergent damages DWR (reversible with reapplication) and can delaminate membranes if done improperly (not reversible). Always use cool water, mild detergent, and air drying for technical gear.

The Bottom Line: What This Means for Your Purchase

Your jacket’s breathability isn’t determined by a single number—it’s determined by the interplay of membrane MVTR, DWR condition, face fabric properties, activity level, and contamination. A 20,000mm waterproof shell with pristine DWR and 9,000 MVTR can outperform a 7,500mm soft shell with degraded DWR and theoretical 15,000 MVTR in sustained rain. But in vigorous activity with high sweat production, the soft shell will feel dramatically drier.

The three critical takeaways:

- The waterproof/breathability trade-off is physics, not marketing. You cannot maximize both; understand which you’re prioritizing based on your activity.

- Lab MVTR numbers are theoretical maximums. Expect real-world performance to be 20–30% lower due to dynamic conditions, contamination, and DWR degradation. Buy with a 2–3x safety margin.

- DWR coating condition matters more than membrane quality. A jacket with a degraded DWR finish breathes worse than a lower-MVTR jacket with fresh DWR. Regular washing and maintenance restore breathability more effectively than buying a higher-rated jacket and neglecting it.